Chapter 2 of potential hindrances to our creative development

**00II: Some of us have the creative spark and some of us don’t**

Number 2 on the list of assumptions that may be dimming our creative power runs along the same thread as chapter 1; it follows the common perception that creativity is a hardwired entity.

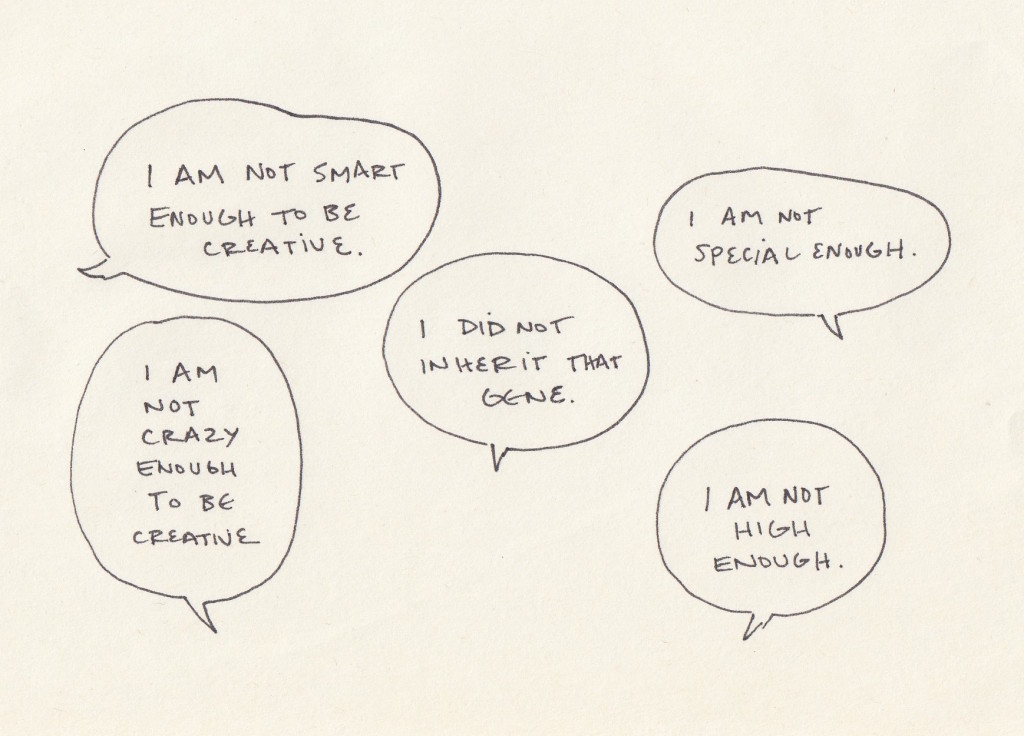

A variety of sub-assumptions come up when someone decides they are short of the creative spark. These are the ones that I’ve witnessed (and in some way have personally experienced) most often:

It’s reasonable to assume that these have come out of images, ideas and experiences we’ve been exposed to that determine what we think a creative person looks and acts like. If we shy away from creative opportunities (or something) based on our belief that we are sparkless, we need to find a way to abandon that solidified image or idea of the spark that we’ve bought into.

What does it mean to be creative, anyway? What is the creative impulse?

Anyone who attempts to answer these questions in a definitive way will only ever successfully restrict the path to a puny flashlight beam. The important thing is, that if we are at all curious about the possibility of the existence of our individual spark, we have to ask these questions for ourselves without giving in to our trained reflex to mimic someone else’s methodology.

But let’s ask a bit later. First let’s see if the above sub-list can be dissolved.

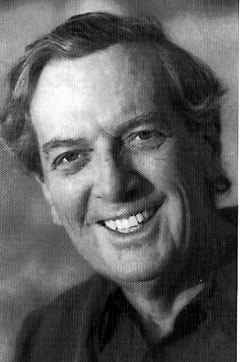

Portrait of Frank Barron. esalen.org

During the 1950s and 1960s, American Psychologist, Professor, and Poet Frank Barron conducted pioneering research regarding the nature of creativity. This consisted of rigorous in-depth interviews and testing of individuals considered to be highly creative in their field including architects, scientists, mathematicians and writers (among these were Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, and Jessamyn West).

Barron found that, contrary to popular belief back then, intelligence (in the IQ sense) had only a modest role in the creative ability of his subjects. His study revealed that creativity is informed by a complex array of intellectual, emotional, sensory, motivational and moral characteristics.

If you were to do a google search right now with something like, “is creativity linked to high IQ?” you’d get multiple sources of various research to confirm Barron’s findings. Hopefully this is enough to strike through the idea that creativity needs an exceptional IQ.

If, however, we have a healthy scepticism of scientific research and question its authority, perhaps it’s more useful to focus on the truly complex nature of the subject; that creativity- what it is, where it comes from and how it’s expressed– can never be precisely determined or fully understood by any means. This is probably a more useful platform to cast a view from when attempting to consider our creative capacity (or lack of) as hereditary.

There are recent studies to support the existence of a creative gene but this research has a specific criteria and is usually motivated by investigations of genius. If we are invested in dismissing our creative potential, it’s pretty easy to find studies to support the absence of a creative gene; on the other hand, there’s significant research out there to make the case that the expansive intricacy of this field can not be held finite by any conclusion based on our current understanding of genetics.

But really, if we have come to the conclusion that the creative gene dodged us, I’m guessing this notion didn’t come from some study. Would you agree that it most likely came from those closest to us, who may or may not have had the best intentions: our families, friends and our teachers?…

Genius, in truth, means little more than the faculty of perceiving in an unhabitual way.

-WILLIAM JAMES