In my last post I began scanning the popular belief that we have to have a certain badge of “crazy” to be creative (“crazy” as in the “tortured/suffering artist” image).

I’ve already tried to lay out evidence to acknowledge the prominence of creative expression in individuals who embrace a vast spectrum of their experience that includes the more difficult, darker and painful facets; it is not a question of whether we suffer enough, it’s more about how connected and true we are to the gamut of our inner selves and our ability to process the flux.

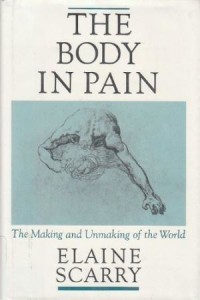

One thing I haven’t denied is the tie between our pain and creative expression. I already hinted at this when I described the ineffable nature of pain at the end of my last post: we can never accurately explain the torment we feel and we are not able to equally experience the suffering of another. Harvard professor and author, Elaine Scarry, describes this phenomenon in her book The Body in Pain:

“Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language. “English,” writes Virginia Woolf, “which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear has no words for the shiver or the headache.” … Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.”

“Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language. “English,” writes Virginia Woolf, “which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear has no words for the shiver or the headache.” … Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.”

Pain and creativity both extend beyond rational language and, therefore, could be considered symbiotic. Do you remember my article, Dropping in the Zone (nothing & all)? I talked about how tapping creative potential requires us to give up a certain sense of self and our habitual thinking processes to enter a non-verbal expanse that isn’t closed off by preconceived ideas and constructs. Pain can be a vehicle to this expanse. Not only that, when we feel an inner upheaval of compounded energy or distressing emotion, there is the (sometimes desperate) need to exorcise it. If we cannot effectively release it in the confines of language, we may reach for a more free form of expression (the infinite list of free forms would not exclude poetry, lyrics or other alternative uses of language– these are also beyond an accustomed use of words). I should probably point out that some pathways for these inner turmoils can be destructive or violent and that creative processes may also be in some way destructive and/or violent (another thing I’ll have to go into more later).

young Finnegan. Photograph by William R. Finnegan.

But is this the best or only path for your creative expression? There has to be more than one way to bypass the rational language cage or perception ruts. What about the experiences that stun us with wonder and awe? There are particular forces and frequencies that our individual vibrations attune to in a way that also allows us to forget ourselves and forgo our definitions. It could be a certain sound, aroma, force of nature or something much more obscure that we don’t seem to have any control over, apart from choosing to answer the call. Author and surfer William Finnegan expresses this in his New Yorker article, Off Diamond Head: “But my absorption in surfing had no rational content. It simply compelled me; there was a profound mine of beauty and wonder in it. Beyond that, I could not have explained why I did it.”

This may sound like we can only hope to get lucky and come into contact with a beauty that resonates and transforms us, while a meeting with torment appears more predictable (not to say that it doesn’t also show up unexpected). We can fairly easily choose to be sleep or food deprived, or put ourselves in dangerous circumstances– I’m guessing that’s why many cultures that have a spiritual quest or rights of passage bring on potential suffering through various physical and emotional challenges to create a transformative space.

But let’s think about how a material can bring on the wordless wonder. For example, if oil paint calls to you and you approach it with an open curiosity, there is a chance to be surprised and stunned with some awe over an unexpected happening. An exploration of a material and process itself may place us in the zone or offer the open channel for our creative energy. In this way we could create the potential to be drawn to a path of enchantment, so long as we don’t sabotage it with expectation.

It’s just too easy to say that all great invention and art come out of tormented individuals. How do we know for sure which works are created in moments of suffering if it’s possible we are either roving a range of gleams and glooms or rocking both simultaneously? What about the debilitating effect of pain? Claude Monet was unable to produce any work for two years after the death of his wife, Alice, in 1911. Perhaps his best work came out of moments of awe while painting. Here’s an editorial that highlights such creative blocks of several artists who are often referenced to uphold the image of the melancholic artist.

William Robertson Davies. 1992 AP Photo/Tom Keller.

I’m not sure I’ve done a very good job expressing how we are a complex fluid spectrum of diverse opposing and composing energies and that there’s a good chance the paths of enchantment and torment are interlaced. What I’ve written may be interpreted as a clear choice between suffering and bliss but it’s not about having to choose one or the other. Any attempt to broaden our experience of the world with a deeper awareness of our inner selves is going to open a creative space. We’ll eventually need to consider the conscious process involved in personally designing the structures that allow us to ditch our limiting patterns of thinking. We may be able to plan these structures but like I’ve said before, creativity happens when you let it.

It’s probably started to sink in that letting the it come through won’t be fast or easy. Some people are tempted to suss out a fast-track to bypass the looming doors of perception. As author and professor Robertson Davies warns, “anything that coaxes us out of the beaten paths of thinking and feeling has value and also presents us with great dangers.” At this time I won’t go into the many dangers that Davies could possibly be alluding to but I will use his words to move on to the: “I’m not high enough to be creative.”

The unpleasant and pleasant should inexplicably overlap in a sort of beautiful feverish madness, in the end imploding under an overwhelming number of interpretive possibilities.

-PETER FISCHLI