I just left off exploring how being influenced to ask first might be a subtle reason we first look to others to show us how to be creative. That isn’t to say it’s a limiting choice to look to others for guidance or to dabble in some established ideas or methods and I’m not referring to technical aspects right now. There are countless existing sources that inform my writing and visual work (you’ve seen me mentioning some of them). By the end of this chapter I’ll get into the expansive possibilities of external influences. For now, though, we’re going to continue sussing out aspects that may contract us.

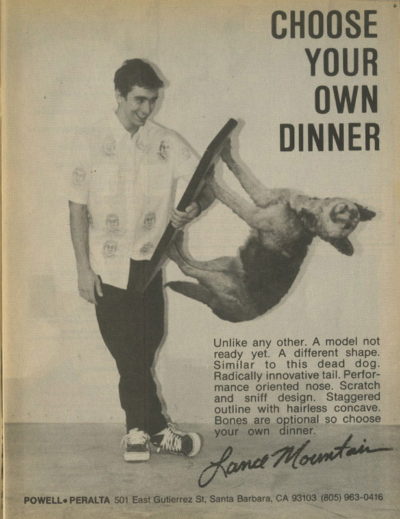

source unknown.

Nearly every adult student I ask has a dark story involving a feeling of having their creative spirit crumpled by someone. This usually involves weighty misunderstandings and/or assessment, some of which I brought up in Chapters 1 & 2. Do you ever wonder why when some people say, “you need to know the rules before you break them” that what really comes across is “follow my rules, or else”? This could be their intention or our perception. You can sort of tell if you are ‘permitted’ and encouraged to ‘break’ the expectations. A genuine guide will do their best to notice when the expectations/guidelines are compressing or liberating us and talk to us about it. I didn’t meet such a guide until I was 33 yrs old. Before that, art class tended to be a boring just-do-what-you’re-told experience and that’s what I came to expect. So where does this propensity to dictate or prescribe a creative process come from?

Drawing by David Shrigley.

I’m aware of multiple possible origins but I want to narrow in on this one: When we happen upon something we like, we tend to want to make a rule about it. Probably because we can’t help trying to preserve and predict the joyous experience or the material thing that came out of the experience or the attention we received. Then comes the desire to name it, replicate it and share it with others. This sharing unfolds with a positive intention but once it moves into enforcement or dogma, there’s a bit of conceit behind it; like, ‘hey, if it was good for me it’s good for everyone f-o-r-e-v-e-r, right?’ We see this a fair bit in institutions. This might be linked to some primordial desire for safety, security and certainty or maybe power and control. And it could be considered a bit at odds with nature.

Guru-stea. Indore, India. Photo- courtesy of my brother.

During a 6 week venture in India, I met a professor and was introduced to the Hindu concept of The Trimurti. Here’s what I understand to be the gist of it and how it may offer insight for creative expression: In a cosmos that is currently expanding, nature actively evolves in a cycle with creativity at the forefront, then preservation followed by destruction and then back to creativity. If we are in the flow of constant creativity, then preservation and destruction follow and allow for more creativity. Now if we attempt to put preservation as the first priority, it invites destruction to come tear it all down; because nature won’t put up with static states or stagnation. If we dictate to our youth (or ourselves) how to make art based primarily on an established standard set of steps (preservation or maintenance), they resist, become apathetic and just complain. Not surprising when trying to repeat the past is a sort of deadened experience.

On the other hand, a desire for preservation is also a part of nature’s design because being oppressed by a prescribed experience inspires rebellion to propel human consciousness toward greater differentiation.

Even one of the most celebrated Canadian classical pianists, Glen Gould, who was renowned for his interpreting abilities once remarked:

“If there’s any excuse at all for making a record, it’s to do it differently, to approach the work from a totally re-creative point of view…to perform this particular work as it has never been heard before. And if one can’t do that, I would say, abandon it, forget about it and move on to something else.”

Glenn Gould. Bettmann/Corbis

It’s highly likely we are going to have a hard time developing our unique creative ability through a maintenance approach that involves doing what we think we should. Knowing the rules does not necessarily mean following them. I’m not arguing against repeating some actions or methods or concepts (it’s pretty much unavoidable) but perhaps the trick is to avoid getting attached to these things and assuming we have to enforce and/or conform to them.

We might use someone else’s rules (a.k.a. ideas, materials, techniques or processes) but a potential sign that they are restricting us is if we end up believing we must act or make things a certain ‘right’ way and results become predictable. This cuts us off from the alive impulse and that’s when we get controlling (being all tense and anxious about making something ‘good’) or we become vacant performers just going through the motions. Then we are not in touch with our creative being and may begin to feel drained by the added resistance.

If I revisit my fort in the living room analogy, this is like constructing our fort with a prefab factory kit or something. None of the parts are special to us, it smells weird and it’s stiff, common and clinical. We haven’t included anything from the living room and we can’t help getting preoccupied with how well we’ve followed the assembling instructions. We fear we might fail and seek to perfect but never feel satisfied with our construction. We aren’t at ease inside of it because it isn’t connected to anything inside of us. And when we try to invite others inside, they will likely feel like they are supposed to enjoy it but may find it leaves them with an empty experience.

So how do each of us know what rules are right for us? Why can’t someone serve them up for us? How do we begin sifting through all of the shoulds we’ve been collecting? How do we handle those instructors who are so insistent that we do it their way?

The advice of the old is like the winter sun; it sheds light but does not warm us.

-FRENCH PROVERB