Chapter 7 of potential hindrances to our creative development :

00VII: All successful art is confirmed when the audience responds exactly as the artist intended.

The ancient practice of dowsing/divining for water.

Wrapping this chapter up at this point may seem hasty. I’m sure it’s noticeable how the content of these chapters are like streams trickling into one river and that some of the streams form a confluence at times. I am merely divining or dowsing for these streams so that you may take it upon yourself to explore their hidden depths. All veins seem to flow back to the same river (that’s always moving toward some ocean-like source) so that some repetition is inevitable but this particular section constellates more closely with Ch8 and Ch9 so I will allow more of the picture to fill in later on. For now I will just review what I barely covered in the last two posts:

My main concern is for those who believe they should create under the above presumption and are cramped up about it. I brought up a few reoccurring snags that could be a source of a creative charley horse:

- we have a habit of focussing on a ‘fixed facts’ kind of knowingness because that is how our education, culture and personal experience has shaped us.

- we are stuck in safe familiar knowledge that gives us control and protects us from the anguish of being misunderstood.

- we’re weighted or stalled out with a sense of impending failure (what if no one gets what I made?)

- we depend on the opinions of others to determine the value and significance of our individual creative expression.

- we are more concerned about making something ‘right.’

- we don’t understand what we’ve made and dread being asked to talk about it.

I had hoped to offer some props by mentioning that most well-known practicing artists confess to some level of not-knowing in their work. I feel pretty safe saying ‘most’ because every creative person I have ever researched has in some way expressed the essential role and significance of mystery in their work. Even if we choose to hone our skills to phenomenal precision, creativity brings in the ‘but anything could happen’ and this is wide open for interpretation. Irish novelist, playwright, short story writer, theatre director, and poet Samuel Beckett was famous for side-stepping explanation-seeking questions about his work. He once declared:

Samuel Beckett directing Waiting for Godot in 1975. Heuer/Ullstein Bild via Getty.

“I produce an object. What people make of it is not my concern […] I’d be quite incapable of writing a critical introduction to my own works.” And when asked “who or what does Godot mean?” he replied with, “If I knew, I would have said so in the play.”

Even though I have grown comfy with not-knowing/entering mysterious realms, I still get cornered by external expectations to explain myself and my work. Now I’m fine with saying I don’t know but it took me a while to find that sure feeling. The belief that I need to know what I am creating and how it will be interpreted by others was reinforced in art school. What is your work about? and who is your audience? was always in our heads and on our backs. These questions could lead to new possibility but at the time I felt forced to insert conjectures that sometimes derailed the living momentum and path of my work; there is something particularly deflating about having to form explanations when you are in the middle of something inexplicable.

I managed to survive (and thrive under) this pressure by finding artists who did not conform to this rushed reaching for answers. I felt a pivotal shift one day when I happened upon some interviews with composer, music theorist, artist, and philosopher John Cage (who I’ve mentioned a fair bit already). I spent six straight hours in the library devouring everything I could find on him because I felt an inner yes! to his attitude toward art. He said things like, “As far as consistency of thought goes, I prefer inconsistency” and “Our intention is to affirm this life, not to bring order out of chaos, nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of it’s own accord.”

Some part of me always knew I didn’t need to have a preconceived idea of what I was making (I wanted a process of mystery ,discovery and connectedness) and I wasn’t interested in knowing any particular way it would be received. But I totally doubted this voice until I heard the anything goes echoed by other artists. Playwright Richard Foreman was also encouraging when he said, “Most people claim that theatre requires an audience. I disagree.[…] I can imagine every member of an audience falling asleep and the play continuing to the end, turning into an objectification of the dream of that audience.”

Scene from Richard Foreman’s play, ‘Old-Fashioned Prostitutes (A True Romance)’. Public Theatre. 2013. Photo credit Joan Marcus.

I’m not saying that we can’t know clearly what we want to create, execute this with success/satisfaction and have our audience respond as we expected. Perhaps we happily paint a landscape and our target audience is landscape-painting-lovers, and we just want them to be able to recognize the landscape we’ve made and like it (forget about the unique feelings they may have toward it). Perhaps we are alright with being in control of everything and knowing how it’s all going to turn out.

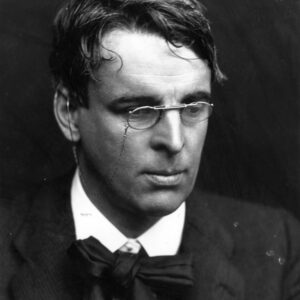

Or maybe we really want our audience to experience something more intangible (like an awakened perception) from our work. We might be tempted to control the odds of this happening. Irish poet and playwright WB Yeats seemed to want to curate his theatre audience when he wrote in the prologue of his last play, The Death of Cuchulain:

William Butler Yeats. 1911. George C. Beresford / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

“I wanted an audience of fifty or a hundred, and if there are more, I beg them not to shuffle their feet or talk when the actors are speaking . . . If there are more than a hundred I won’t be able to escape people who are educating themselves out of the Book Societies and the like . . . pickpockets and opinionated bitches.”

Like Yeats, we may wish to edit out common vulgarity in our audience to give our work a better chance to be heard or maybe protect it (and ourselves). There’s a good reason why a musician deliberately chooses to play for a quaint bar scene and avoids a stadium stage. There are ways to select our audience without dictating someone’s individual experience— like the time and place we show our work. Personally, I can’t help wondering about the benefits of having the most diverse audience as possible; I bet there’s a really good chance of new learning and expansion when all walks of life get to meet our work.

Whether we get to a position where we want to have a particular message or meaning and a certain audience to receive it or we are patiently waiting for the work and the audience to reveal itself on many levels— we don’t need to worry about such things when we are in the creative flow. Even if the message or audience comes first, giving us the initial kick or inspiration, there is no need to get attached to this initial form.

The nub I’m fumbling to expose here is that our creative expression lives and breaths in spaces and times that we cannot even fathom. It’s kind of absurd to think we have to know what it is and how it speaks. I always have the feeling that art is so much more than I am capable of thinking about so anything I say about it is just a sort of goo-goo gaga translation. I keep this in mind when I am enjoying talking about it and when I find meaning in it or I don’t.

So many of my students get cuffed when their work doesn’t look like the ‘thing’ they wanted and when a viewer sees or feels something other than what they intended. This seems to have a lot to do with society teaching us to stick to the framework of a coherent narrative. No big deal if we notice when we are trying to keep confusion away by pushing out any mystery or contradiction and if we take this as a sign we are exiting the creative field (and probably denying the voice of our deepest self).

My soul is a hidden orchestra; I know not what instruments, what fiddlestrings and harps, drums and tamboura I sound and clash inside myself.

All I hear is the symphony.

~FERNANDO PESSOA

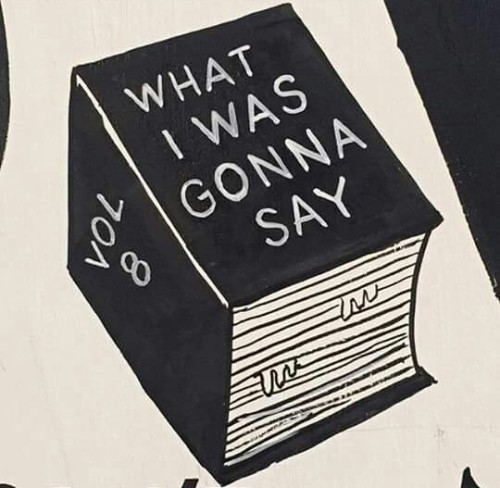

[**Title image: Artist Simon Evans]

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.