Chapter 8 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

I was just saying how our formal education (with its historical influences) tends to deliver the presumption that a creative work has a singular meaning that can be reached on an intellectual level. If we are accustomed to being given wordy explanations and expected to grasp or build them, how do we relate to a work of art (or any creative expression) beyond this?

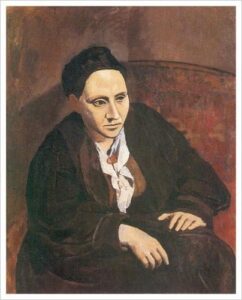

Portrait of Gertrude Stein. Pablo Picasso. 1906.

In a rare (1934) interview, novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector Gertrude Stein was asked to explain her “Van or Twenty Years After. A Second Portrait of Carl Van Vechten” and proceeded to bawl out her interviewer a bit:

“Look here. Being intelligible is not what it seems. You mean by understanding that you can talk about it in the way that you have a habit of talking, putting it in other words. But I mean by understanding enjoyment. If you enjoy it, you understand it.”

Have you ever noticed a feeling of deep connection that comes with enjoyment? When I am listening to the music I love, I feel it in my body and being as if it is a part of me— it’s like I get the music and it gets me. Have you ever taken a shine to something and understood it without knowing how you know? I’ve watched my grandfather absorbed in taking an antique tractor apart without a manual and when I asked him how he knows how it all goes back together he said, “I just know.” Even if I pressed him to explain to me how he knows, he wouldn’t be able to tell me. It’s not necessary to put words to or give reasons for such experiences to validate them because they are beyond language and thought.

This reminds me of a part from the 2014 film Get on Up, which is a biographical drama about the life of singer James Brown; in this scene Brown asks the drummer to make a change that saxophonist Maceo Parker doubts (Brown first points out how he considers every instrument a drum):

James Brown: Fellas, what’s them shiny things y’all holding over there?

James Brown: Fellas, what’s them shiny things y’all holding over there?

Together: Drums.

JB: Now we all got our drums. Now when you’re playing a drum, it don’t matter what key you in, what bar you in, what planet you on.

Maceo: But, Mr. Brown, Clyde’ll be in a different time than the rest of the band. It doesn’t work musically.

JB: How many hit records you got, sir? Fellas, does it sound good?

Together: Yeah.

JB: Does it feel good?

Together: Yeah.

JB: God made your ears. You didn’t make ‘em. You gonna argue with God’s ears? If it sounds good and it feels good, then it’s musical. So play it like I say play it.

Language has the capacity to both limit and expand; sometimes it can be cruel and reductive but it can also make something accessible. It allows us to communicate more rapidly, interpret and evaluate our world and create or express meaning. We tend to use it in a way that over-utilizes the intellect though, so that we ignore other dimensions of our being like feeling and intuition— which is not to say that language can’t offer connection and expression to these dimensions. For instance, a poet uses words to access the mysteries of existence that cannot be touched by a common way of speaking. But then when we take poetic language and put it in analytical terms to think about, we often maim its power to reach beyond habitual or rational/logical thought. I realize we could find enjoyment in an analytical process but this is about possibilities beyond that avenue. Author and Nobel Prize recipient John Steinbeck pointed to our compulsive explanation-seeking:

You’ve seen the sun flatten and take strange shapes just before it sinks in the ocean. Do you have to tell yourself every time that it’s an illusion caused by atmospheric dust and light distorted by the sea, or do you simply enjoy the beauty of it?

Another pivotal moment that came up during my art school experience happened when the mentor I brought up in Chapter 6 delivered the following Leo Steinberg quote to the class:

Another pivotal moment that came up during my art school experience happened when the mentor I brought up in Chapter 6 delivered the following Leo Steinberg quote to the class:

“The thought takes form as a picture–and let’s not ask whether this is what the artist had thought while he made it. It’s what the picture gives you to think that counts.”

This is from the essay, Jasper Johns: The First Seven Years Of His Art, in the book Other Criteria. At this bell-ringing moment I realized that I had been approaching works of art in the way that John Steinbeck describes— seeking to grasp something the artist really meant; as if a logic-reason-explanation would be more real and legit. I wasn’t considering my experience of the work beyond the whole do I get it or do I not get it? What a load off to consider there is nothing to get! (as in, nothing or not one right answer).

Not only did this completely alter and open my attitude towards the creative expression of others but it also set me free from thinking I had to deliver preconceived messages in my own work. I’m not saying that I stopped finding meaning in creative expression, I just started to close the gap between my individuality and universal knowledge; it became fun to consider what a picture gave me to think about. This may all sound like what is commonly called ‘ego-centric’ but I am referring to a part of us that is beyond the ‘ego’ (and I’ve been regarding the creative impulse as a force beyond the ego). I am not talking about being ‘separate’ individuals like a me versus you or them— I want to consider our connection to the oneness or interconnectedness of existence that may be found through our uniqueness; as if tapping our singularity is the way to feeling/being part of the whole. (I’ll get into this more further down the road).

Okay, but what if we don’t enjoy a work of art? How do we relate to it if it confounds or irritates the hell out of us? What does this have to do with our creative capacity?

To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim.

OSCAR WILDE

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.