Chapter 8 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

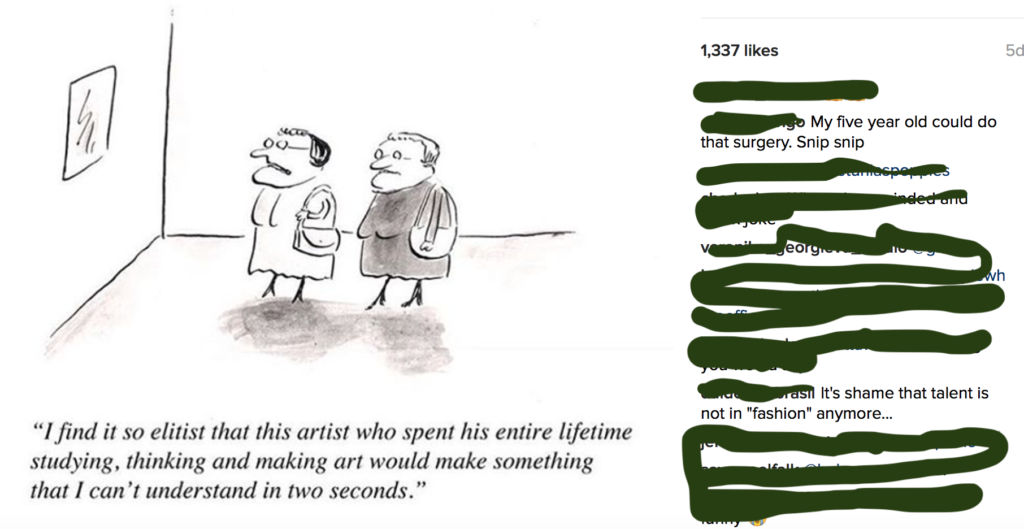

In the last article I sat down with the possibility of understanding creative works through our enjoyment of them. But is all art meant to be simply enjoyed? We’ve probably all met a work of art that baffled or disappointed us and there’s a good chance we felt our defensive judgy talons lash out with something like, “my kid could paint that!” or “how much did that cost?!”

Naturally, we are free to enjoy or reject any artistic expression. But is there something important beyond an experience of liking and not-liking? For various reasons, a part of us has a big problem with feeling left out. This has come up before— that the creative impulse is linked to our deepest sense of self. Feelings of inadequacy, confusion or disconnect around artworks can get us going with complaints or negative opinions to shield or defend our ignorance; barking at what we can’t see while feeling unseen. Part of us just wants to be right (I know what I like!); to sort of dominate the work of art. When it comes to art that we can’t immediately connect to, it’s easier to dismiss it as dumb, non-sensical or useless to avoid any personal discomfort or challenge. Some may even want to declare all art trivial (non-essential or non-practical) or establish some core value around what’s familiar (like, the only art that matters is realism or historical works). Does any of this attitude seem open, receptive or expansive?

In his 1891 essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism, poet and playwright Oscar Wilde wrote:

“If a man approaches a work of art with any desire to exercise authority over it and the artist, he approaches it in such a spirit that he cannot receive any artistic impression from it at all. The work of art is to dominate the spectator: the spectator is not to dominate the work of art. The spectator is to be receptive. He is to be the violin on which the master is to play. And the more completely he can suppress his own silly views, his own foolish prejudices, his own absurd ideas of what Art should be, or should not be, the more likely he is to understand and appreciate the work of art in question.”

Oscar Wilde Monument. 1997. Danny Osborne. Commissioned by Guinness Ireland Group. Merrion Square, Dublin, Ireland.

I’ve already sufficiently radiated the vital necessity of receptivity when it comes to our personal creative expression. And I’ve pointed out several glitches that arise from gripping rigid ideas of what art is or isn’t. Some of my own foolish prejudices at one time were: art is supposed to be pretty, right? It’s supposed to be made with some mastery of skill. And it has a purpose, doesn’t it? I’m not saying beautiful art made with skill that has a purpose isn’t a possibility in a creative field. But have you ever wondered where your ‘taste’ comes from? Are there limitations to what we’ve been exposed to as ‘art’? Who made the ‘beautiful’ art we were taught to appreciate? Who decided we should appreciate it? What if we feel like the Mona Lisa is just “meh”? Does any of this screen us from our unique capacities?

I understand that a flood of questioning like this can come across as super intense, disorienting and maybe even pointless. But if we truly want to connect with our creative nature and are bottle-necked with shoulds that have formed from our passive interactions with existing art, we’re going to need to start some sort of dislodging inquiry. To take it down a notch how about we ask, what would be a more receptive approach to art that confounds or repels us?

In my fourth year of art school I had a professor who required us to do full day class critiques. Most of us weren’t a fan of these because they were totally exhausting and often had a numbing effect. During one of these weekly marathons, he asked us to look at someone’s work for a full 30 minutes without speaking. I inwardly groaned and then reluctantly stared into a series of drawings. At first I felt the resistance of the exercise (why are we wasting time with this shite?!) and then I felt myself just relax into it (fine, whatever) until I wasn’t really thinking about anything. Near the end of the 30min mark, I had a peculiar floating sensation— the work appeared to be sort of moving or breathing and new insights and connections began to strangely arise. Like on some rookie psychedelic trip I think I actually blurted out, “Hey! Something’s happening!”

This experience helped me clue into the value of taking some time, exercising patience, and getting into a relaxed open state when approaching something that I have written off as boring, confusing or irritating. I now understand that I had expected all art to amuse me—like it was its job to connect with me without any intention or contribution on my part. I didn’t realize that art could be asking something of me. When we find ease and comfort in what we love and enjoy and we find a satisfying connection through our attention to those things, we tend to want to stay in that sweet zone all the time; it’s easy to reject and dismiss anything unfamiliar or uncomfortable as its failure— as in, it just doesn’t do it for me.

Source of comic unknown (found on instagram). Notice the comments that came up on the right.

In her essay, ‘Art Objects’, English writer Jeanette Winterson speaks about her initial ignorance and lack of interest in the visual arts; knowing nothing about painting and therefore getting little from it. When she began to approach painting with an open curiosity that asked more of herself than of the artwork she says:

“I had fallen in love and I had no language. I was dog-dumb. The usual response of “This painting has nothing to say to me” had become “I have nothing to say to this painting.” And I desperately wanted to speak. Long looking at paintings is equivalent to being dropped into a foreign city, where gradually, out of desire and despair, a few key words, then a little syntax make a clearing in the silence. Art, all art, not just painting, is a foreign city, and we deceive ourselves when we think it familiar. No-one is surprised to find that a foreign city follows its own customs and speaks its own language. Only a boor would ignore both and blame his defaulting on the place. Every day this happens to the artist and the art.

“I had fallen in love and I had no language. I was dog-dumb. The usual response of “This painting has nothing to say to me” had become “I have nothing to say to this painting.” And I desperately wanted to speak. Long looking at paintings is equivalent to being dropped into a foreign city, where gradually, out of desire and despair, a few key words, then a little syntax make a clearing in the silence. Art, all art, not just painting, is a foreign city, and we deceive ourselves when we think it familiar. No-one is surprised to find that a foreign city follows its own customs and speaks its own language. Only a boor would ignore both and blame his defaulting on the place. Every day this happens to the artist and the art.

We have to recognize that the language of art, all art, is not our mother-tongue.”

Perhaps if we approach confusing artworks as if we’re aliens dropping in on a new planet with it’s own strange beings, languages and customs, it’s a bit more obvious that we have much to discover; you know, before deciding that what we see, hear, smell, taste and feel is ugly and we want no part of it. But why should we bother putting any energy toward learning from what we don’t like? What do we get out of this?

True art, when it happens to us, challenges the ‘I’ that we are.

JEANETTE WINTERSON

[*Title image: Another David Shrigley]