Chapter 8 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

In Part 2, I was beginning to unwrap the question, is all artistic expression meant to be enjoyed? After mentioning some resistance around this I left off with: and if it isn’t, what do we get out of art that we don’t understand or enjoy?

One thing I’ve been trying to bring attention to is the idea that our experience with creativity is not one-sided. There is an exchange; an unmistakable current that flows between us and the work. Whether we are creating, looking at, listening to, tasting or moving to creations we are always giving something and receiving something. I would go as far to say that artworks have their own thoughts and intentions to interrelate (though they may not think like us). What do we give the work? By taking in a work of art we are offering our current perception— all of our experiences, beliefs, feelings, ideas and concepts are projected onto it. What can we receive from it? That depends. When we find it difficult to access or connect to an artwork, it could be an indication that it’s asking us to expand beyond the limits of our present awareness; offering us a channel to enlarge and refocus the scope of our lens to the world.

In his book Why Read, professor, writer and furniture-maker Mark Edmundson critiques the common contemporary way we are taught liberal arts (through analysis and theory) and looks beyond this doctrinaire methodology:

In his book Why Read, professor, writer and furniture-maker Mark Edmundson critiques the common contemporary way we are taught liberal arts (through analysis and theory) and looks beyond this doctrinaire methodology:

“What’s missing from the current dispensation is a sense of hope when we confront major works, the hope that they will tell us something we do not know about the world or give us an entirely fresh way to apprehend experience. We need to learn not simply to read books, but to allow ourselves to be read by them.”

How do we allow ourselves to be read by a book? Have you ever read or listened to a story or lyrics in a song and felt like it understood you? Perhaps a character or scene expressed something that previously evaded you and then you suddenly (without effort) felt and realized a part of yourself that you didn’t even know existed. Or maybe by stepping into a story you were freed from some smothering harsh limit you had concluded about the world so that life seemed to take on a revived freshness. It’s not like we’re being brainwashed or lectured by such language or imagery, it’s as if by reading, looking or listening we are actively co-creating some new meaning (giving/receiving or reading/being read) so that we may decide for ourselves how to live.

This sense of co-creating while reading is what French literary theorist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician Roland Barthes called the ‘writerly text’. In his book The Pleasure of the Text (1973) Barthes suggests that such writing destabilizes expectations and requires our active participation as readers (bringing our own subjective perception to the table) to construct the meaning. He distinguished this from what he called a ‘readerly text’ which is the form we are more accustomed to through formal education. By contrast this text is transparent— having a pre-determined and fixed meaning in which we are only a passive and inert consumer of the author’s product. It is written to hide any elements that would open it up to multiple meanings. If we think we are supposed to receive the artist’s message in art, aren’t we treating works of art as if they are ‘readerly texts’?

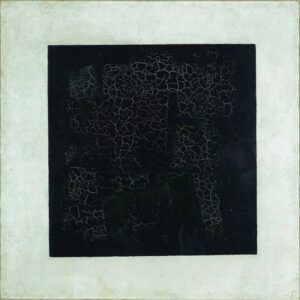

Black Square 1913

© State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

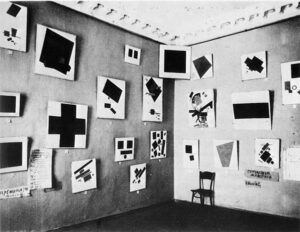

Let’s consider something a bit more challenging. Like, how do I let myself be read by a painting of a solid black square? Imagine being in Petrograd, Russia back in 1915 and stumbling into the group exhibition Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10. This is where kiev-born artist Kazimir Malevich first showed the world his (in)famous painting, Black Square. A lot has happened since then to expand collective thought about what a painting could be but back in 1915 this was met with much more resistance than my kid could paint that. Part of the uproar back then was due to the placement of this painting— Malevich hung it in what is known in Russia as the “red” or “beautiful corner” (where the walls form a corner and meet the ceiling— see second pic further below) which was reserved for religious icons. These sacred images/objects traditionally represented a window into the heavens, into eternal life. Was Malevich asking whether a black square— an image without storytelling, figuration or natural imagery— could be a gateway to a spiritual realm? It’s obvious he was challenging the shoulds of a painting but what did he say about it?

Kasimir Malevich, Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10, Dobychina Art Bureau at Marsovo Pole, Petrograd, Russia. 1915.

In his book The Non-Objective World (1927), he wrote:

“In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.”

And here’s a couple more cryptic things he said about it:

“It is from zero, in zero, that the true movement of being begins.”

“I have only a naked icon without a frame (like my pocket) the icon of my time.’

You may be thinking, well if I knew some of this background ahead of time it would be easier to consider and maybe connect with this painting of a black square. This may be the way to get some sort of ball rolling with a work that stumps us— to do a bit of research about it. We may even find divergent expansive paths through that research. But I want to remind you (what Leo Steinberg suggested) that while it may be curious, interesting or fascinating to learn what an artist thought when they made their work, the important thing is how and what the work speaks to us— even if it contradicts what the artist thought.

Back to that whole— how do I let this black square read me?: When I find myself face to face with a work of art that totally baffles me or gets my hackles up I begin to ask it some questions like, what are you trying to say to me?, why don’t you seem like art?, what am I expecting from you? what have I never considered before?… John Cage once said, “The first question I ask myself when something doesn’t seem to be beautiful is why do I think it’s not beautiful. And very shortly you discover that there is no reason.” As I’ve said before, the point of such questions isn’t to necessarily formulate answers— it’s just a way to open up into a wonder-receptive state.

A disarming encounter with art is a gift to take our foot off the gas of our constant interpreting/evaluating pedal and coast into a momentary non-dual alive possibility (there’s no good/bad, right/wrong, this/that etc.) We don’t need to expect anything to happen, we can just walk away content to have been open to a new experience. An insight or revelation might bubble up much later or we may simply be left with a mysterious feeling. Nothin’s gonna happen if you try to force it, though (remember?).

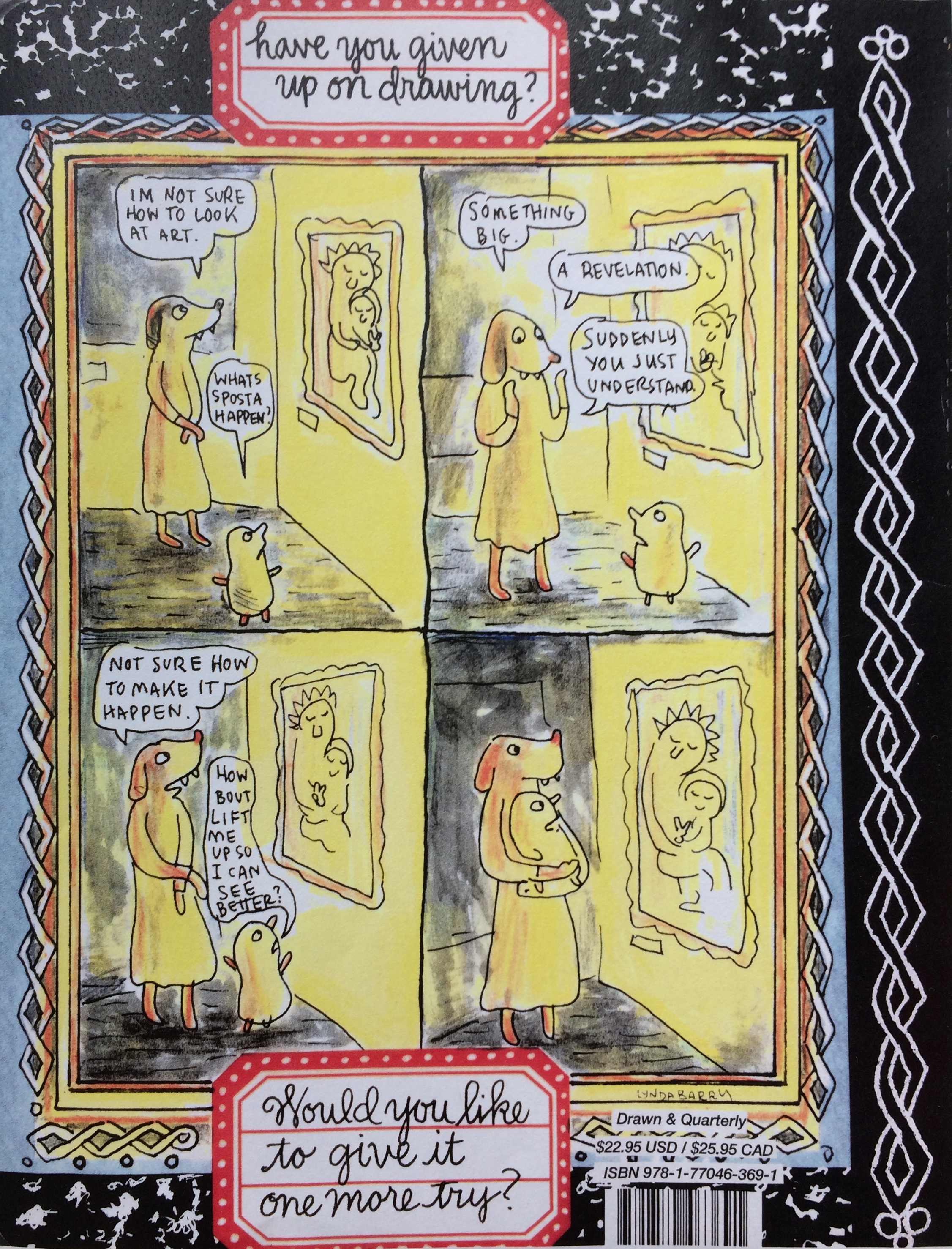

The back cover of my copy of Lynda Barry’s recent book ‘Making Comics.’

Okay, but what if someone’s creative expression is just sooo boring and we don’t want to ask it anything? We think of boredom as our rejection of something but what if we flip this around? Like literary critic, writer and teacher Lionel Trilling once put it:

“Some of these books (Kafka, Joyce, Proust etc.) at first rejected me; I bored them. But as I grew older and they knew me better, they came to have more sympathy with me and to understand my hidden meanings. Their nature is such that our relationship has been very intimate”.

It’s funny that we choose boredom over wonder. Both are super leisurely but certain boredom (the whiney kind) waits to be entertained while standing behind a closed door. In a way, we need to feel boredom to know what wonder is but when we hold onto our boredom (constantly standing by for someone or something to amuse us) it’s exhausting— and then once we are amused we tire of that easily as well. I am reminded of this every time I am in front of a slouched and bleary-eyed high school English class.

None of this is to say that we have to cheerlead every work of art we encounter. We don’t have to like it, enjoy it or get it but why not be curious about it? Appreciating art that we easily enjoy helps us to align with what we love while wondering about art that evades us has the potential to open doors to personal expansion and transformation. If we want to know ourselves better, we have to bring in something different from someplace else… and this can taste funny at first.

I want to know life and understand it and interpret it without fear or favor.

THOMAS WOLFE

[Title image: my own photo if the wildest sun dog I’ve ever seen.]

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.