Chapter 6 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

At the end of the intro to this chapter, I left off with the question: How is imagination different than knowledge? I’ve been cruising in the country of this question throughout this blog but the shifts in atmosphere seem to expose new sights and sounds. As always and just so we’re clear, when it comes to pinpointing anything here I am happily always at a loss.

Within this current I would actually like to kick off with another query: Why is it that we assume we create from some image in our mind? Did someone tell us this? As a child, when I turned my entire bedroom into a theatre for My Little Pony/ She-Ra/ Smurf/ Care Bear/rock collection escapades I was told that I had a wild imagination. When I made creases in my blanket on my bed to form roadways for some Hot Wheels I was told the same thing. When I made stacks of drawings and told stories about them someone would say, “wow, it’s amazing what you dream up in that head of yours!” But I don’t recall following any pre-formed idea in my mind about any of these things; I was just making it up as I went along (what a fraud!).

Within this current I would actually like to kick off with another query: Why is it that we assume we create from some image in our mind? Did someone tell us this? As a child, when I turned my entire bedroom into a theatre for My Little Pony/ She-Ra/ Smurf/ Care Bear/rock collection escapades I was told that I had a wild imagination. When I made creases in my blanket on my bed to form roadways for some Hot Wheels I was told the same thing. When I made stacks of drawings and told stories about them someone would say, “wow, it’s amazing what you dream up in that head of yours!” But I don’t recall following any pre-formed idea in my mind about any of these things; I was just making it up as I went along (what a fraud!).

When I watch children ages 5-12yrs drawing or painting (I’ve been doing this with wonder for about 20yrs), I can tell when it’s an event; when the work is unfolding in front of them and they are responding and making choices as they go. Have you ever noticed that a child’s ‘rough’ copy feels more alive than their ‘good’ copy (or, if you avoid kids, maybe you have felt this with your own work)? Children are naturally more present and don’t usually approach a ‘rough’ copy as anything rough at all. It’s not like how I might vaguely sketch out a drawing— with the awareness that it’s just a guide. A child is usually all in from the beginning and then they often ‘check out’ when asked to repeat something. If they don’t check out, they sometimes get all frustrated and perfection-seeking in trying to replicate what they did when they were in a much different state (sound familiar?).

Perhaps a sticky perception forms when we’ve been asked to draw, paint, write or make things that already exist. Have you ever noticed how children tend to draw and paint certain things the same way (I mean you as a child, too…or maybe you right now)? You know, the sun in the corner? Perhaps the images below will ring a bell:

I’ve even asked my 91 year old grandfather about this and he is pretty sure he drew these (except for the two clouds on the rainbow— he couldn’t remember ever doing that one). I wonder if we are picking up these ‘symbols’ in the same way we pick up language (through mimicry) so that these images tend to be more tied to our language centre. Any living flower is remarkably unique and anyone could invent an original looking flower but when you ask most children to draw a flower, they ‘imagine’ and reproduce the above symbol. I don’t think this is because they have a limited imagination. They are probably just recalling the memory of what they were shown/told before. In this way ‘imagining’ it first is more steeped in knowledge.

In a school setting, when I ask a class of students (any age, really, but there are always exceptions) to draw anything they want I usually see a lot of the same style and imagery (in middle school/ high school, the above images graduate to eyes, skulls, a more detailed flower, sports logos, etc.). It appears as though these students lack imagination but perhaps there is a lack of awareness or understanding about the use and reach of the imagination.

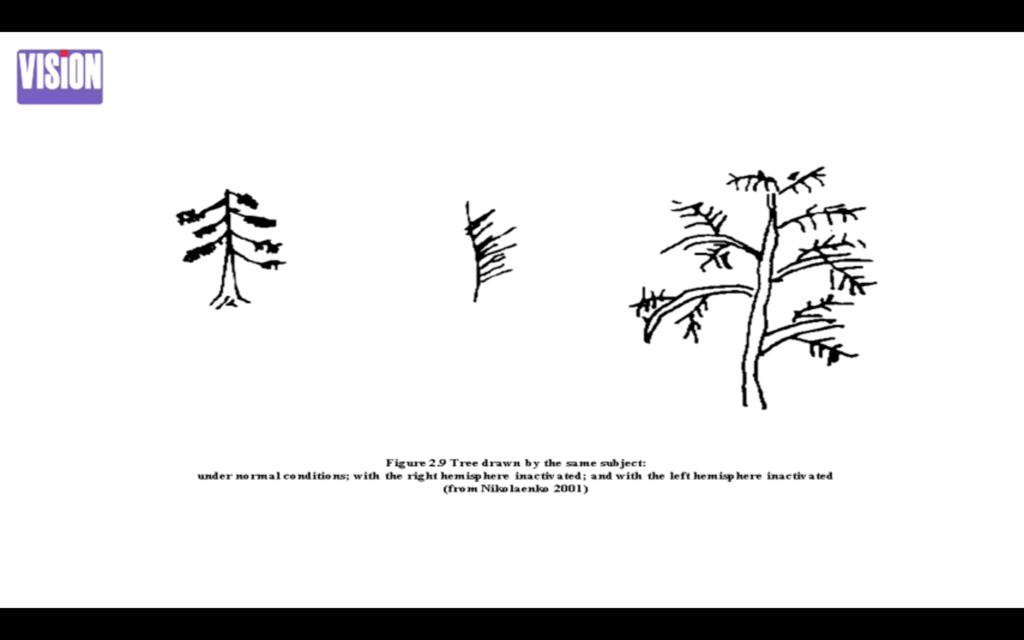

You may recall when I mentioned some brain research back in this article. Iain McGilchrist, who is a psychiatrist and author of The Master and His Emissary: The divided brain and the making of the Western World, shares some pretty sweet discoveries about how the human brain shapes the world we see. We now know that the brain isn’t simply left brain-logical and right brain-intuitive (there’s a lot of complex crossover action) but McGilchrist has found it is still profoundly divided. Some of his research involves the behaviour of stroke patients which allows him to observe one side of the brain and how it functions while the other side has been shut down. In this YouTube lecture , he mentions a subject who draws a tree: a) under normal conditions, b) with the right hemisphere inactivated and then c) with the left hemisphere inactivated. Check out the image below that came from this lecture. Notice how the centre drawing is a far less detailed tree with only its right side. McGilchrist says that the left brain hemisphere is only interested in what’s on the right and drawings are expressed in 2-dimensional symbols. If we tend to default to fixed symbol drawing, perhaps this points to our restricted use of imagination as a habit of being more left hemisphere dominant or exercising reason and language centres more often. So how do we get around that?

A slide I borrowed from McGilchrist’s online lecture.

Within the 6-12yrs crowd, I will ask students to choose a subject and then (depending what medium we have to work with) show me a version of it that they have never seen before. So if they are painting a rainbow, they are creating one they have never seen anywhere in the physical world (including t.v., books, internet etc.). I never show examples and I don’t demonstrate so if a child is stuck I ask questions like: well if no one has seen this rainbow, does it have to look or act like any rainbow we’ve seen? If this rainbow can do whatever it wants, where is it? What is it doing? This is literally like flipping a light switch and all* (I haven’t experienced a student completely shutting down with this but that is possible) students come up with something exciting and new all on their own. I couldn’t tell you if they traded the symbol image of a rainbow for a new one in their mind and worked from that, but somehow they went from a compartment of the known to reaching into the expanse of the unknown with very little guidance.

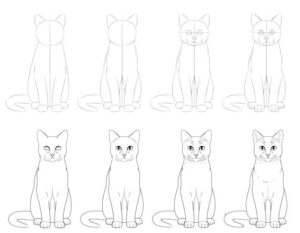

Sample How-to-Draw steps.

I have no way of proving this but it seems to me that most of us learn to associate imagination with art in school (or at home) where we are introduced to creativity in a way that emphasizes the known more than the unknown. Like being shown how-to-draw (craft) step by step exercises or how to plan a story in a linear worksheet format– which tend to speak to left brain processes. There’s nothing inherently wrong with these exercises but they teach us to predominantly use our imagination as a tool to picture what already exists (& to match an external expectation). All of that getting it right and making something ‘good’, seeps in pretty early so that we seek fixed ideas in our mind that we try to reproduce. Or we feel a bunch of pressure to think of ideas and get snagged on the I don’t have any ideas in my head to start with. It’s probably starting to sound parroty at this point but we just need to balance this out with some ventures into the unknown so that we are bringing more of our right brain hemisphere (and our hearts) to the party.

So how do we extend the reach of our imagination without thinking so damn much?

I am doing my best to not become a museum of myself.

NATALIE DIAZ

[Title gif: source unknown– but dang I wish I knew!]

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.