Chapter 7 of potential hindrances to our creative development:

00VII: All successful art is confirmed when the audience responds exactly as the artist intended.

If we are dipping a bucket into the unknown depths of our creative pool, the above assertion could come across as a pretty big should: like we’re supposed to know what we are creating and will know we have succeeded when everyone ‘gets it’. OOF. How many of us respond to this with something like, well I don’t know what I’m doing so I can’t start until I do or how am I going to make sure everyone ‘gets’ what I’ve made?

Something to wonder about is why this expectation is still prevalent when so many artists have spoken against it. Writer George Saunders countered it when he commented on overcoming his fear of attempting an exploratory run at a profound idea:

“My novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, is the result of that attempt, and now I find myself in the familiar writerly fix of trying to talk about that process as if I were in control of it.

We often discuss art this way: the artist had something he “wanted to express”, and then he just, you know … expressed it. We buy into some version of the intentional fallacy: the notion that art is about having a clear-cut intention and then confidently executing same.

We often discuss art this way: the artist had something he “wanted to express”, and then he just, you know … expressed it. We buy into some version of the intentional fallacy: the notion that art is about having a clear-cut intention and then confidently executing same.

The actual process, in my experience, is much more mysterious and more of a pain in the ass to discuss truthfully.

[…]

An artist works outside the realm of strict logic. Simply knowing one’s intention and then executing it does not make good art. Artists know this. According to Donald Barthelme: “The writer is that person who, embarking upon her task, does not know what to do.”

Obviously, it’s natural to presume that someone who is good at what they do knows what they are doing to varying degrees. But perhaps we take it for granted that it’s just easier to identify or quantify the ‘knowing’ aspects of someone’s skill or performance (a guitarist’s ability to hit crisp chord transitions, for instance). I keep bringing this up but maybe we’re just in the habit of interpreting a creative experience or expression through the one sided lens of our logic/reason; the part that can pinpoint and judge and prefers to be in control. Or it could be that our creative efforts have always been judged or marked by someone’s technical craft criteria and we have decided it’s much safer to know what we are doing and how our audience will respond. To follow and share our deepest creative impulses is to expose our hearts and soft bellies to ridicule and, worse, misunderstanding. Writer Steven King has spoken to this vulnerability:

Steven King has expressed feeling misunderstood by the Stanely Kubrick film make of ‘The Shining’.

The most important things are the hardest things to say. They are the things you get ashamed of, because words diminish them – words shrink things that seemed limitless when they were in your head to no more than living size when they’re brought out. But it’s more than that, isn’t it? The most important things lie too close to wherever your secret heart is buried, like landmarks to a treasure your enemies would love to steal away. And you may make revelations that cost you dearly only to have people look at you in a funny way, not understanding what you’ve said at all, or why you thought it was so important that you almost cried while you were saying it. That’s the worst, I think. When the secret stays locked within not for want of a teller but for want of an understanding ear.

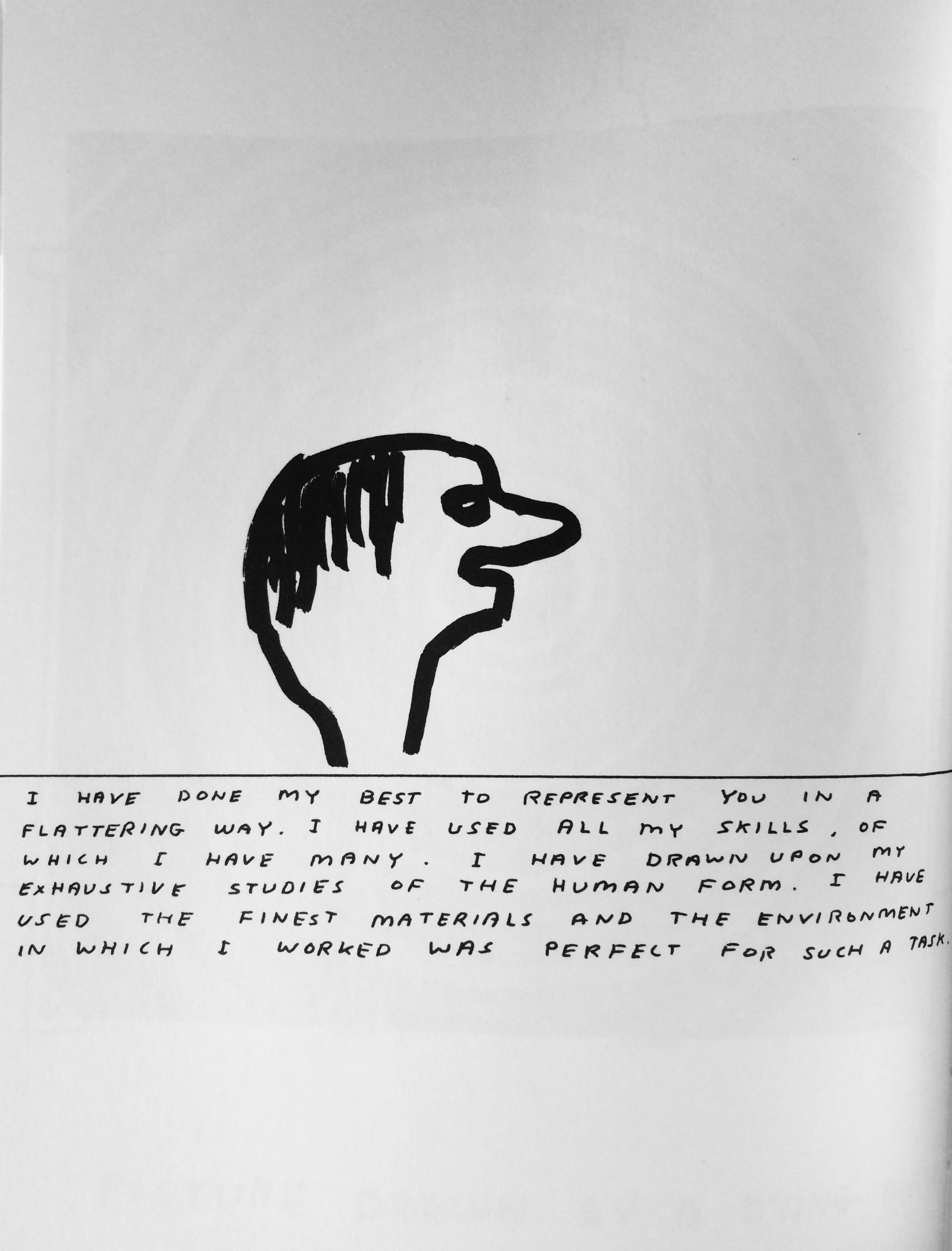

Have you ever shown your drawing to someone who interpreted it as something way off base? Like you were going for a zebra and they said, “aww, cute duck.” Never mind that you had neglected to add the ears, stripes and two of the legs to your exotic creature. A duck? C’mon.

I bring up this scenario because so many of us have had the experience of making something ‘special’ to us that was totally misunderstood and felt gutted by this— as if our essential being had been dismissed. And it often becomes a trend that began in our childhood. It’s almost a kind of Russian Roulette when a child approaches me and asks, “do you like what I made?” followed by something like, “can you see what it is?” If I answer incorrectly, I might as well be stabbing this child in the soul.

When working with children, I have a couple ways of getting around this dreaded set-up. Instead of answering the identify-what-I-made question, I’ll respond with questions in more of a game-like fashion where I might ask, “what does this character like to eat?, where does it like to sleep?, does it have friends?, is it magical?”, etc. Or I might just say, “I’d like to hear you tell me about what you made.” Naturally, there will be a time when a child really just wants to test us. In this case, I’ll say what I see and if I end up saying “nice duck” about a ‘zebra’ and the child gets upset (feeling failure), I can ask questions around missing information such as, “how many legs does a zebra have?, does it have ears? what colour is its coat?” This way, I am allowing the child to connect to her own knowing about a zebra and what she may have left out of her drawing (versus a critical angle like, “well you forgot the stripes and two of the legs so how was I supposed to know!”). There’s a good chance she’ll know those answers and then she is free to adjust her work or not. This encourages a stronger connection to inner knowing/guidance and creative impulses.

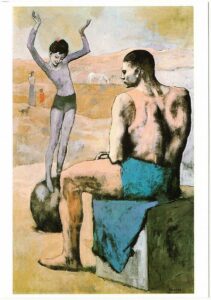

Acrobate à la Boule (Acrobat on a Ball). 1905. Pablo Picasso.

It’s needless to say that communication through a picture is something pretty extraordinary. Especially some mark-making we’ve scratched on a page. I’ve talked about the thrill of having done something right and good when we can hold up our work and receive the response we were after. Some might even say it boosts confidence. I would argue that it’s more about propping a sense of security and acceptance when we’re seeking external validation. I’m not saying we don’t need security and acceptance— obviously we need to learn what it means to be a functioning member of society.

The structure of our education system (and most parenting) is set up to establish skills and awareness so that most of us can adapt to the mainstream or consensus reality. We’re expected to know a lot of manners, ‘facts’ and to share and agree with many ideas that maintain peace and prosperity (and we should end up with a useful sense of what would upset the balance and create all levels of conflict…although we currently have a bit of a narcissism problem). But, as I’ve said, this model of education has great difficulty approaching our individuality— especially when it clashes with the mainstream. Art (when embraced as infinite possibility) gives us a chance to stretch outside of this (somewhat circus-y) ring of training and control to balance both our learned skills and individual nature; so that we are able to bring our skills to life.

It’s a pretty thin sense of self and confidence when it hinges on another person’s response to me or what I’ve made. How can I trust my deepest individual self when all of my reliance is on the opinions of other individuals? And how will anyone understand my unique nature and expression when they are looking at me and what I make through their own unique nature? How do we reconcile this?

The chemistry of mind is different from the chemistry of love. The mind is careful, suspicious, he advances little by little. He advises “Be careful, protect yourself” Whereas love says “Let yourself, go!” The mind is strong, never falls down, while love hurts itself, falls into ruins. But isn’t it in ruins that we mostly find the treasures? A broken heart hides so many treasures.

SHAMS TABRIZI

[Title image: A page out of my personal copy of ‘The Book of Shrigley’. David Shrigley. Chronicle Books.]

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.