Chapter 8 of potential hindrances to our creative development :

**00VIII: We don’t understand art unless we get what the artist intended.**

While the last presupposition mainly dealt with getting uptight and freaked out when our personal creative expression is being looked at, this one concerns limitations born out of the way we look at the creations of others. Even if we have come to terms with allowing mystery to exist in our own work and accept different interpretations of it, there is still a chance we continue to believe that we should understand exactly what an artist meant when they made their work. Why would we clutch this belief, and how does it get in the way of our own creativity?

Perhaps you can relate to the strain of trying to get the ‘right’ message from a work of art. Have you ever thought (consciously or unconsciously) something along the following lines?: if I know the artist’s specific message, this could mean I’m also a creative genius and maybe I’m better (or more special) than the people who don’t get it. If I don’t get it, however, I guess I’m a lesser human being with a shallow or absent creative capacity. I admit to having tasted both of these impressions and it makes me wonder why our sense of self gets tangled up in this getting it or not getting it.

Personally speaking, this is a perception I gathered during my formal education— because, you know, from a child’s perspective (in a competitive environment) whoever scores the highest on any test is better than everyone else. In primary, secondary and some post-secondary school, I was exposed to works of art as if they were owl pellets in a lab where you operate with tweezers until you can pull out and piece together what the owl ate. Like we never really read poems or stories, we deciphered them. The teacher always had the answer key to the style, tone, theme, meaning etc. and we had to match those standard answers like every other kid in the country. Even though this felt off, why didn’t I question it? I just figured that the authors/artists must have explained their works and our teachers had access to this information.

As I pointed out in Chapter 7, I later discovered that artists tend to avoid giving any final word about their work and explanations usually come from the audience. Novelist, short story writer and essayist Flannery O’Connor once wrote a fairly scathing reply to an English professor who wrote to her on behalf of three department members and ninety university students. They were seeking her confirmation for their interpretation of “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and got told:

Flannery O’Connor. (Emory University Archive).

The interpretation of your ninety students and three teachers is fantastic and about asfar from my intentions as it could get to be. If it were a legitimate interpretation, the story would be little more than a trick and its interest would be simply for abnormal psychology. I am not interested in abnormal psychology. . . .

The meaning of a story should go on expanding for the reader the more he thinks about it, but meaning cannot be captured in an interpretation. If teachers are in the habit of approaching a story as if it were a research problem for which any answer is believable so long as it is not obvious, then I think students will never learn to enjoy fiction. Too much interpretation is certainly worse than too little, and where feeling for a story is absent, theory will not supply it.

My tone is not meant to be obnoxious. I am in a state of shock.

It may seem like she is saying they had the wrong answer about her story but O’Connor is pointing out the limitations (and arrogance) of interpretation when it is over-intellectualized; when it leaves out personal feeling and enjoyment.

Obviously there are common symbols, meanings and cultural influences expressed in the arts that can be taught (and tested). But when a fixed research-problem approach to creative expression dominates, we learn to distrust and completely disregard our spontaneous and deepest personal responses to literature, drama, visual arts, dance etc. Even when we are asked for a personal response, by middle school it usually comes through a filter of I don’t give a shit about this or what is the answer my teacher is looking for? or what will impress my teacher? When I didn’t understand a painting or a poem etc. in school, I felt confused, left out and inadequate— not intellectual enough or weird enough or something. I would often decide that the work was boring or stupid and I didn’t ask questions.

The fear of admitting we don’t know something and feeling like an idiot is often reinforced on a social level. American musician (Silver Jews), singer, poet and cartoonist David Berman says it best in this excerpt of his poem, Self-portrait at 28:

The fear of admitting we don’t know something and feeling like an idiot is often reinforced on a social level. American musician (Silver Jews), singer, poet and cartoonist David Berman says it best in this excerpt of his poem, Self-portrait at 28:

“If you were cool in high school

you didn’t ask too many questions.

You could tell who’d been to last night’s

big metal concert by the new t-shirts in the hallways.

You didn’t have to ask

and that’s what cool was:

the ability to deduce,

to know without asking.

And the pressure to simulate coolness

means not asking when you don’t know,

which is why kids grow ever more stupid.”

In a way, it’s like we all received training to disconnect from our inner knowing. There are libraries of history we could unpack in terms of authority claims over the human spirit or soul or individual self. Now seems like a good time to ask: If we don’t trust our own experience of the mystery of another’s creative expression, how do we trust our own mysterious impulses? Beyond interpretations and explanations, how do we understand a work of art?

I want a picture to seem as if it had grown naturally, like a flower; I hate the look of interventions— of the painter always butting in.

-WILLEM DE KOONING

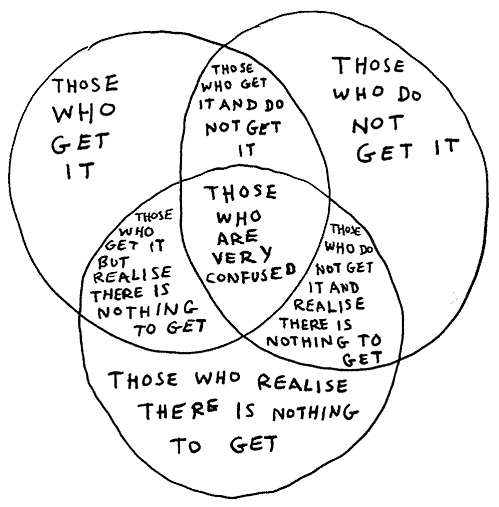

[*Title image: yup, artist David Shrigley http://davidshrigley.com]

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.