When copy work makes us come alive (that is to say that no matter what anyone else thinks, we love and are filled with vitality when we reproduce an image or subject), where is the essence of creativity in that?

Even for those who are initially enamoured by the act of making a realistic duplicate, it is likely that they will eventually stall or get bored of making straight up replicates. Perhaps you’ve heard the sad story of someone who had so much “artistic talent” (in the way of accurately depicted work) and just wasted it: they just stopped making any work. So what is it that encourages or propels someone to continually make more work in this way? Besides money, I mean.

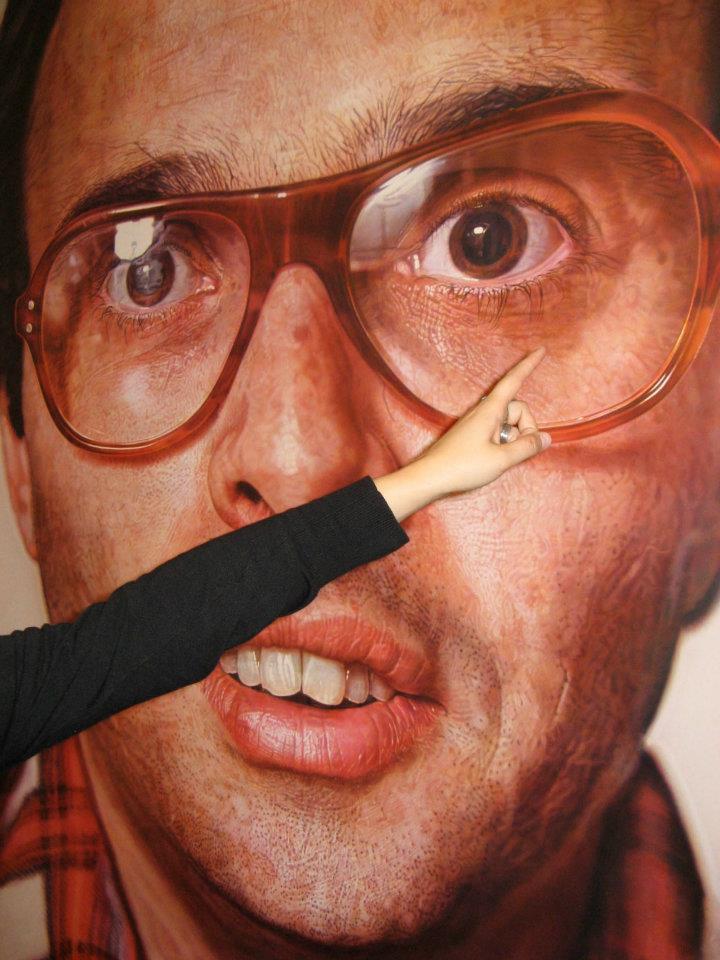

For renowned portraitist, Chuck Close, it has something to do with a deeply personal experience. Close is very well known for his photorealistic/ super-realistic portrait paintings that he constructs mainly through a methodical grid or system driven process. I was inches away from one of his large scale portrait paintings at the MET in NYC and the realism was crazy impressive (that’s my shot of this event at the top of this article).

In a recent interview Close said he paints such portraits “to take images of people that matter to me and commit them to memory in the best way I can, which is to slow the whole process down, break it down into lots of little memorable pieces.” I guess that’s not so unique until we learn that he experiences severe face blindness or prosopagnosia; a condition that makes recognizing faces from one day to the next nearly impossible. This raises all sorts of complexity beyond the skill or craft of his work. In an earlier interview Close admitted:

“I was not conscious of making a decision to paint portraits because I have difficulty recognizing faces. That occurred to me twenty years after the fact when I looked at why I was still painting portraits, why that still had urgency for me. I began to realize that it has sustained me for so long because I have difficulty in recognizing faces.”

Self-portrait with Cigarette. Chuck Close. 1967-68.

Even after Chuck Close experienced a spinal artery collapse that left him temporarily paralyzed from the neck down, it wasn’t long before he had a brush in his mouth then taped to his wrist. So yeah, this is within the mysterious and powerful space of creative expression.

If we feel that reproducing a subject is where there’s excitement or we were once excited by this and now feel bored and limited by it, we may begin to play around with our choice of process or subject matter and how it relates to what/how we sense the world. I’m not suggesting a thinking process. This is the realm of exploration in the not-knowing. As I said before, this can be a scary place if we already have the craft skills. It may be a real challenge to set aside our adopted expectation and judgement. I’m afraid I cannot give any specific instruction on how to do this. We can explore broad strategies further on, though (like the one mentioned at the very end of this post).

For those who are relieved to consider that realistic copy work is not necessarily creative expression and you are someone who thought you had no creative spark or ability based on that criteria, you may be in the most ideal space for discovery. By deciding that we are not creative there’s a possible nothing-to-lose ability that offers us a nice push into the space of exploration: I may as well give it a shot because, what the heck, I’m no artist and I’m not going to be making art. In this expansive space we are free of someone else’s pre-existing idea or concept of art and it’s a sweet opportunity to tap our unique process.

The choice not to do something is in a funny way more positive than the choice to do something.

If you impose a limit to not do something you’ve done before, it will push you to where you’ve never gone before.

-CHUCK CLOSE