Chapter 9 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

…I was just beginning to describe how I would bring my multidimensional self and ways of knowing to a descriptive-style art critique so that I am relating from my heart, mind and body. For the academic types out there, I might characterize these as realms of relatedness that include ontology, axiology, epistemology and methodology. I only mention such fancy terms to do my usual acknowledgement of the infinite complexity of a creative field (and to open some gateways for exploration) but my purpose here isn’t to go into a bunch of specifics and give the impression that the unfolding of this process is super complicated— because basically, we don’t have to know and control a bunch of moving parts. Phew.

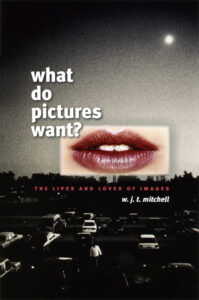

Having said that, I feel compelled to offer a few more particulars around the nature of pictures because I think it may help clarify the purpose for bringing our hearts, minds and bodies to the table of the art critique. American scholar, W.J.T. Mitchell introduced me to the curious idea of the metapicture which are pictures about pictures— that is, pictures that refer to themselves or to other pictures (pictures that are used to show what a picture is). If your head hurts now, it’s about to go up a notch.

In an interview with Asbjørn Grønstad and Øyvind Vågnes from the online magazine Image & Narrative, November 2006, Mitchell refers to his essay What do Pictures Want? and describes some of the complexity around images:

The widest implication of the metapicture is that pictures might themselves be sites of theoretical discourse, not merely passive objects awaiting explanation by some non-pictorial (or iconoclastic) master-discourse. In relation to the domesticating tendencies of semiotics, for instance, with its taxonomies of signs and sign-functions, I like to think of the image as the “wild sign,” the signifying entity that has the potential to explode signification, to open up the realm of nonsense, madness, randomness, anarchy, and even “nature” itself in the midst of the cultural labyrinth of second nature that human beings create around themselves. In What Do Pictures Want? I put this in terms of the following analogy (roughly paraphrased):

The widest implication of the metapicture is that pictures might themselves be sites of theoretical discourse, not merely passive objects awaiting explanation by some non-pictorial (or iconoclastic) master-discourse. In relation to the domesticating tendencies of semiotics, for instance, with its taxonomies of signs and sign-functions, I like to think of the image as the “wild sign,” the signifying entity that has the potential to explode signification, to open up the realm of nonsense, madness, randomness, anarchy, and even “nature” itself in the midst of the cultural labyrinth of second nature that human beings create around themselves. In What Do Pictures Want? I put this in terms of the following analogy (roughly paraphrased):

“when it comes to images, then, we are in something like the position of savages who do not know where babies come from. We literally do not know where images come from, or where they go when (or even if) they die.”

The metapicture, then, is also a figure that helps to explain the often-observed uncanniness of images, their ghostliness or spectrality, their tendency to look back at the beholder, or seemingly to respond to the presence of the beholder, to “want something” from the beholder. I don’t think we can properly understand images without some reckoning with vitalism and animism. And I do not mean by this some kind of regressive return to primitive thought, but (as Levi-Strauss so often insisted) a taking account of the persistence of the “savage mind” at the dialectical heart of whatever we mean by the modern. I would also want to urge that we not see this exclusively in anthropomorphic terms, as if the vitalistic or animated character of the signs and symbols we create around us could be exhaustively described in terms of personification or prosopopoeia. Certainly, the conceit of the “desiring picture” or the “animated icon” may involve an analogy with human attributes, but the features of vitality, animation, and desire (at minimum, appetite) also permeate downward, into the animal and vegetable kingdoms.

This is why, in What Do Pictures Want? I want to stress the non- or inhuman desires of images, and explore the neglected concept of totemism (with its emphasis on natural iconographies—plants, animals, and even minerals, including fossils, of course), in addition to the more familiar and anthropocentric concepts of fetishism and idolatry. My aim in What Do Pictures Want? is thus not to project personhood onto pictures, but to engage with what I call “the lives and loves” of images.

If you got sleepy reading this or completely blanked out (maybe you even skipped it), that’s totally fair. This is a lot to contemplate. It’s enough to recognize the strangely powerful responses we have toward images we encounter day to day and acknowledge that we often behave as if pictures were alive— as if they possess power to influence us; persuading and seducing and demanding things from us (on a very basic level, if you see an image and want to buy it, fight it, or hold it as a connection to a loved one, you know what I mean). Needless to say, we are influenced by pictures beyond the intellectual (analytical) level.

Screen shots from Walt Disney’s 2009 Animated Film, ‘Up’. Directed by Pete Docter.

Perhaps you’ll agree that standing or sitting around a work of art and talking about it is a totally bizarre affair. For me, it’s like entering an alive wilderness. Creations of images and sounds have their own unique nature (sometimes beyond time and space) and don’t behave in the orderly ways of language (which is strung out in a line and held to linear time). That being said, we do set out to talk about them— so in the actual moment of an art critique I allow any descriptive thought or emotion or sensation to bubble up to the surface in a meandering pattern. My classmates would be following this meandering pattern as well— spontaneously bringing up philosophy, psychoanalysis, ‘artspeak’, personal stories, feelings, sensations etc. that seem to drift toward, around, through and away from the artwork. Someone might blurt out something fairly non-sensical and then have to keep talking to make sense of it.

As far as the role of the body, I once had a sensation in a critique that involved a sudden knot in my stomach and an overwhelming feeling of a threat that occurred while I was holding someone’s work. A moment later, the artist collapsed in an anxiety attack. This may sound coincidental, outlandish or spooky to some and I can only say that this sort of thing is just a part of the peculiar nature of an art critique.

I’m aware that this all may sound a bit like chaos but it’s more like a cosmos. A descriptive critique is like a bud that unfolds and blooms in all directions at once in a complex pattern— its coherency is best taken in all at once. It is super helpful to have a good facilitator in this process, though; especially when everyone is new to it. This guide helps to track and connect what has been said and to rein in any excessive drifting with redirecting questions.

If any of this seems ethereal or overwhelming, perhaps I may offer some encouragement when I say that I have engaged classes ages 5yrs- 90+yrs in this practice. All I do is ask everyone to describe (and do their best not to judge) what they see and allow any sensations or emotions to be expressed. I usually have to remind everyone that contradictory responses are welcome (like if someone says they feel uplifted and another person says the work is unsettling) as art does that thing I’ve already discussed— holding opposites in unity.

You may be wondering how any of this is supposed to benefit the artist or help with their growth and transformation. Seems like a good time to revisit Mira Schor’s question: “How does one make it possible for someone to change “by themselves?”

Cosmos is a Greek word for the order of the Universe. It is, in a way, the opposite of chaos. It implies the deep interconnectedness of all things. It conveys awe for the intricate and subtle way in which the Universe is put together.

~CARL SAGEN

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.