Chapter 9 of potential hindrances to our creative development continued…

**00IX: An ‘art critique’ is a necessarily painful affair.**

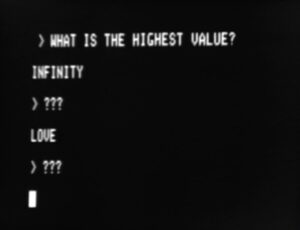

At this time, it would make sense to ask: If we are not receiving an assigned value (or rating/grade) and no one is telling us how we should make our work, what are we getting out of an art critique? How can it help us change by ourselves?

source unknown.

Back in Chapter 3, I went into a fair bit of depth on the subject of seeking an external authority to judge or rate and direct our creative expression so you may want to hit that up again (or just have it in mind) before going further. Beyond this, we might presume that an art critique would be centred around a problem-solving approach (which is important in foundation teaching). But Mira Schor has brought up the downside of this:

“…since a problem-solving exercise tends to hint at ‘a’ solution. Clearly all would pay lip service to the idea that it is just the working through any set of limitations which is useful about these exercises. Yet an art curriculum which depends heavily on problem-solving tends to be oriented towards formalism, and implies a set of correct solutions.”

Since these writings have been peering beyond correct solutions and causes and such, we could bench the problem-solving approach on the sideline (where it may sub in if we need it). While at art school, I was re-appreciating the TV series X-Files and nearly jumped up when the character Fox Mulder said: “Dreams are the answers to questions that we haven’t yet figured out how to ask.” I had this immediate insight that art could also be answers to questions that we didn’t know how to ask yet and, therefore, it might guide us toward more expansive questions. As author Lawrence Weschler advised: “Better to spend 90% of your time honing the questions, and after a while the subject will open up.” This has a more expansive quality to it than focusing on a problem to solve which has a way of keeping us at the level of the problem.

It may feel like I’ve been pulling multiple rugs out from under you: so, we’re not going to ask someone how to make our work, or how to make it better or whether it’s good or not and we are not going to explain anything upfront and we won’t be trying to solve problems…cool cool. So, ah, why are we doing this?

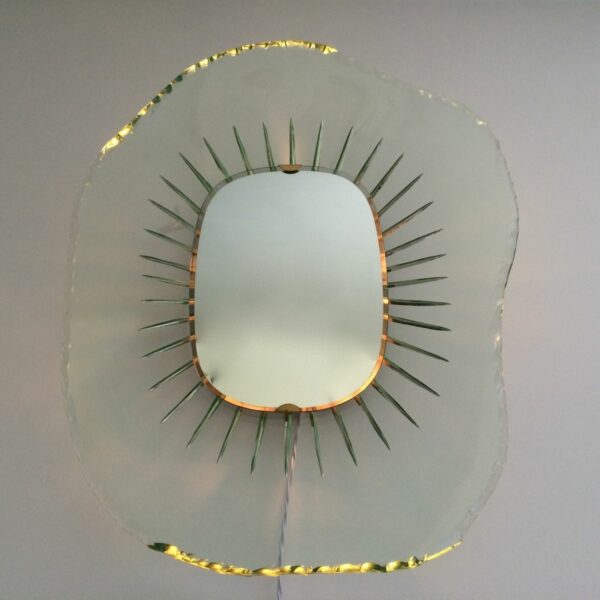

As an artist showing my work for feedback, I am personally more interested in increasing connections than I am in solving problems. In his book, Honey from the Rock, Lawrence Kushner wrote, “Everyone carries with them at least one piece to someone else’s puzzle” and this is what I am open to in a descriptive art critique. The tricky part is that we don’t know what and where these puzzle pieces are. However, if we consider a work of art as a mirror to the viewer (reflecting back to them all of their ideas, beliefs and perceptions) and not a window to me the artist that created it, it’s almost like the viewer can act as another mirror to help reflect and reveal the hidden messages in me (connections I couldn’t make on my own). Basically, a work of art can give us a chance to see aspects of ourselves through someone else’s eyes.

I gave an example of this uncanny mirror-like process back in part 2 when I described a critique where my classmates kept bringing up ideas around institutions of Art and Science and I was inspired toward a deep inquiry while being invigorated to create more work. No one told me what to do but to characterize this as ‘change by ourselves’ is a bit misleading. A collaborative descriptive process allows me to tap the vast relatedness of the participants— all of their knowledge, experience and connections— while getting to sort out the patterns and ideas that resonate with me on a deeply personal level. So my transformation is not a solo mission that I can control— it never really is as I am always dependent on my relatedness to all things- people, places, time, sentient/non-sentient creatures etc.(that all have their own agency); however, I do get to follow my own curiosity and excitement.

Here’s a short list of some of the wisdom that I have gained from my visual practice through a descriptive art critique in the most general terms:

- greater awareness of coherent complexity; seeing the patterns of interconnectedness; everything exists in relation to something/someone else.

- divergent thinking practice

- recognizing the illusion of individual facets of reality studied in isolation as fixed forms.

- awareness of the limitations and potential of perception

- the need for dissolving resistance

- a transitional way of being/adaptability.

- less judgy/ giving up opinions in favour of more ideas.

- more open/compassionate

- the ineffable can be expressed

- everything in nature is infinitely varied

Who made this?

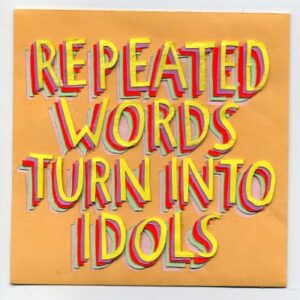

The whole unfolding of a descriptive art critique (as I’ve described in this Chapter) is designed to bypass the intellect’s attempts to classify and return to a resting state. It’s that part of us that French novelist Gustave Flaubert described as:

“The rage for wanting to conclude is one of the most deadly and fruitless manias to befall humanity. Each religion and each philosophy has pretended to have god to itself, to measure the infinite, and to know the recipe for happiness. What arrogance and what nonsense! I see, to the contrary, that the greatest geniuses and the greatest works have never concluded.”

Art (or life) is not a coagulated set of ideas but a dynamic experience. As French poet, essayist and philosopher Paul Valery put it: “To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees.” There is a grounding (no need for rugs) effect when we realize that trying to fit the order of the world’s complexity to the order of words is a curious kind of deception that can be approached lightly. We can be in the dance of images, sounds, thoughts, memories and sensations that exhilarate us and delay separation and closure by the intellect. Perhaps this is a part of what Russian writer Leo Tolstoy meant when he said:

“The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of a doubt, what is laid before him.”

This reminds me of that old Zen saying that goes something like A finger pointing at the moon is not the moon. The finger is needed to know where to look for the moon, but if you confuse the finger for the moon itself, you will never know the real moon. This is to say (as I understand it) that words themselves are not the truth but they can guide us toward the experience of truth. That is, if we agree that truth is something we live—in many dimensions with many points of view.

If the eye were an animal, sight would be its soul.

~ARISTOTLE

*Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. I do my best to track down original sources. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s). Email me for credits/removal.