I just spent the last entry reaching for a possible broad understanding as to why some authorities or instructors are hell-bent on us following their rules (obviously, individual people have unique and complex reasons for trying to control other people or outcomes). I also discussed how adhering to someone else’s methods and tastes may have caused us to doubt or fear our ability to independently explore our particular creative impulses or to be cut off from those impulses. But are there specific inhibiting methods and rules to consider?

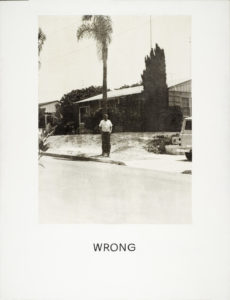

Wrong. 1967. John Baldessari. Photoemulsion with acrylic on canvas. 59 x 45 in. (149.86 x 114.3 cm)

Let’s say I’m curious about film photography. Once I get my hands on a camera, I might want to get familiar with technical things like my aperture settings and shutter speeds. If I’m developing my own pictures then I need to know about the chemicals and all the necessary steps/rules so that I end up with pictures in my hand. There is room for experimentation even at this technical level and we ultimately decide if we are pleased with the outcome. The process alone may be enough for us; I might be super amped on conducting my experiments but then remain detached from my results. Possible creative numbing may show up when we start fretting about standards that dictate what makes a ‘good’ picture. When we start hearing a voice in our head saying things like, “am I allowed to do this?”, “am I doing this right?”, “will people like this?”, this is most likely a fallback on what we learned from a prescribed experience. Also limiting, is an outside voice telling us “hey, you can’t do that!”

Conceptual art pioneer, John Baldessari, has made several works that question the validity and usefulness of judgements based on conventional criteria. Check out the image above titled ‘Wrong’. This picture would be judged as having poor composition–just look up the Rule of Thirds to see what I mean. Baldessari was asking, how can ideas or impulses be judged as right or wrong if they are expressed as personal responses? He has described his work as “what I thought art should be, not what somebody else would think art would be. You know, received wisdom, what you would get in school. And so a lot of my work was about questioning this received wisdom.” You might want to take a look at this 5min video on his work: A Brief History of John Baldessari. Countless individuals throughout history in all fields have asked such questions and went beyond conventions and most aren’t even famous. (I’ll be mentioning the famous ones because those are well documented)

Martha Graham. Lamentation, 1930. Photo. Leabo, Karl.

Martha Graham, who is often called the mother of Modern dance, is another one of these individuals. Even though she did not fit the criteria to be a ‘good’ dancer in the 1920s, Graham was aware that Ballet training at the time was very much a doctrine of movement imposed on the dancers. She rejected its strict syllabus and sought to draw out the movement that should arise naturally from the dancers themselves- “to simply rediscover what the body can do.” Her 1930 performance of Lamentation, didn’t involve her dancing about grief; she sought to embody grief and this left the audience puzzled and miffed. She has said, “I felt at the time I was a heretic. I was outside the realm of women. I did not dance the way that people danced. I had what I called a contraction and a release. I used the floor. I used the flexed foot. I showed effort. My foot was bare. In many ways I showed onstage what most people came to the theatre to avoid.”

Even if we don’t intend to commit ourselves to an art practice and are more the quiet type when it comes to challenging the status quo, for the sake of our private-like creativity we could still question authority. Let’s go back to that photography scenario. Perhaps you’ve signed up for a photo class or you’re surfing youtube demos just to pick up some knowledge and techniques. When it comes to judging your work you may be thinking that a photography instructor, successful artist, curator or art historian has more knowledge and experience than you and therefore must have answers for your work. I’d say it’s totally possible that they could offer some insight; not the same as saying to us, “you know what you should do?” and then following that with a specific how-to. That’s actually a collaboration if we accept it; because now their perceptions, ideas and taste would be in our work. That’s cool if we choose to collaborate.

For someone to make a correction or suggestion for our work without an invitation is pretty presumptuous; it’s like saying they know all of the infinite possibilities and can determine the best possibility for our personal creative expression. Is there anyone out there with this all-seeing power? And what happens when we are on our own with no one to tell us how to make our work? Many art students struggle to make work post graduation due to an adopted dependency on external authority interference. Remember: asking, not telling, is guiding us toward the essence of our creative impulses. Sometimes even just asking ourselves can reveal guidance. When I am faced with someone shoulding on my work, I’ll hear them out but their opinion has no bearing.

I want to be clear that this is not the same as what some might call, ‘avoiding criticism’ or being ‘resistant to change.’ When I am asking for guidance as an art student, I seek support for my inquiry and I want to be free of anyone’s projections of prejudice, judgement, theory, desire etc. I need someone to act as a mirror to help reveal and reflect back the hidden messages in me. I’ll return to this in the chapter regarding ‘critique.’

So there may be multiple sources that exist to help you with some technical aspects but our creative process takes some searching beyond technical tips (we can circle in on this more down the road of these posts). I recently read the following in Paul Feyerabend’s autobiography, Killing Time: “Byzantine art constructed faces in a severely schematic way, using three circles with the root of the nose as their centre. The length of the nose equalled the height of the forehead and the lower part of the face–and so on, as described in the Painter’s Manual of Mount Athos. The rules do give us faces–but in a single position (frontal), without details and without character.” And Feyerabend was a mathematician, scientist and philosopher among other things.

If you realize that it could be about knowing some rules but not necessarily following them, and that no one can really tell you how to make your work or single handedly present the structure you need, how is breaking rules useful beyond getting us past conventions of good composition?

Integrity has no need of rules.

-ALBERT CAMUS